Sentencing in federal court is very different from almost all state courts, especially Texas. First, plea bargaining is not as common in federal court. In State court, there is usually a lot of back-and-forth during plea negotiations, and these negotiations usually take place at scheduled court settings commonly referred to as “Docket.” In federal cases, there are usually limited plea negotiations, the proceedings move very quickly, and negotiations are rarely completed at the scheduled court appearances. Once the decision to plea “Guilty” is decided, the court issues a sentencing scheduling order with very important and strict deadlines and court dates. There is a great deal of research, drafting, investigation, and preparation between the “Guilty” plea and final sentencing. The U.S. Federal Sentencing Guidelines are a critical part of arriving at the final sentence, but there is a great deal more to consider. Below are the applicable sentences imposed according to the federal guidelines and the sentencing process. This outline cannot substitute for the counsel of an experience federal criminal defense attorney.

Brief History About the Federal Sentencing Guidelines

The United States Federal Sentencing Guidelines went into effect in 1987. Before this, judges had almost unlimited discretion over their sentences, and the U.S. Parole Commission was in charge of determining when offenders would be released on parole. However, Congress and the Supreme Court recognized that this created a wide disparity in sentences for the same crimes.

To create more consistency and transparency with sentencing, Congress established the United States Sentencing Commission, an agency within the judicial branch of the federal government. This commission is made of up to seven voting members who are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. To maintain bipartisanship, no more than four members of the same political party can serve on the commission at one time. In addition to these seven members, the Sentencing Commission employs a staff of about 100 attorneys, social scientists, and other criminal justice experts. With these competing interests, the technicalities of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines become more apparent.

Congress also passed the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, or SRA, in an effort to regulate sentencing. The SRA gave the Sentencing Commission two main tasks:

- Establish and regularly amend the Federal Sentencing Guidelines.

- Issue reports to Congress that recommend changes to sentencing laws in federal legislation.

The SRA and the U.S. Sentencing Commission significantly changed the federal sentencing system. Today, there is much more consistency in sentences, but sentences also tend to be harsher than they were before 1987.

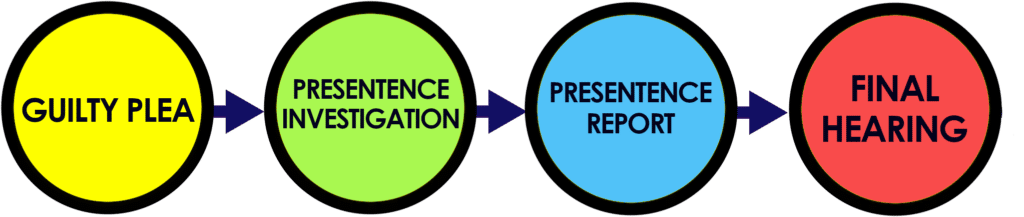

Steps in the Process

The process is a complicated process; however, it can generally be broken down into the following four steps based on the Federal Sentencing Guidelines:

1. Guilty Plea

The overwhelming majority of cases are resolved by a guilty plea rather than a trial verdict.If someone is charged by indictment, and the Government will not dismiss the case, then the person charged has two options: (1) Plead guilty and move on to sentencing; or (2) If a defendant refuses to enter a plea, the court must enter a plea of not guilty, and the case will proceed onto trial. If a defendant has decided to plea, the court will schedule a hearing to accept the plea and schedule sentencing procedures and proceedings.

At that hearing, the court will engage in what is known as a “colloquy” as required by Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure 11. During this hearing, the court will advise a defendant of his or her rights, then ask questions to be sure the defendant understands those rights, and find out if the defendant wants to waive those rights and enter a plea of “Guilty.”

Then the judge makes sure the plea is voluntary. The court addresses the defendant personally in open court to determine whether the plea is voluntary and make sure the plea did not result from force, threats, or promises (other than promises in a plea agreement).

Once the judge determined a defendant intends to plea guilty freely and voluntarily, then the court must determine if there is a “factual basis” to support a conviction. This is usually accomplished by the signing and filing of a “Factual Resume” that contains facts stipulated (agreed to) by the defendant and Government.

If there is a plea agreement, the court will go over this with the defendant. The court can either accept, reject, or defer a decision on the plea agreement.

Once all of this is done, the court accepts the plea of “Guilty” and finds the defendant guilty. Then the case moves on to the presentence investigation phase.

2. Presentence Investigation

By the Court

After a guilty plea or a guilty verdict at trial, a United States Probation Officer will conduct a presentence interview with the defendant. The following topics are usually discussed during this interview:

- Family history

- Employment history

- Education history

- Medical history

- Mental health history

- Substance abuse history

- Financial circumstances

The information obtained by the interviewer is supposed to help the judge determine the appropriate sentence. The defendant’s defense attorney should always attend the presentence interview. The attorney should be well-versed in how answers might affect the sentence and a defendant’s right to decline to answer questions.

The interview is important for several reasons, but one of the most important is how it might affect a Guideline reduction for Acceptance of Responsibility. Two or three levels may be deducted from the offense level for Acceptance of Responsibility. This reduction is for truthfully admitting the offense conduct, and truthfully admitting or not falsely denying any additional “relevant conduct” for which the defendant is accountable under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. A person does not have to volunteer or affirmatively admit “relevant conduct” beyond the offense of conviction in order to obtain a reduction for Acceptance of Responsibility. A defendant may remain silent in respect to relevant conduct beyond the offense of conviction without affecting the reduction. However, if a defendant falsely denies (or frivolously contests) relevant conduct that the court determines to be true, then the court will likely determine the defendant acted in a manner inconsistent with acceptance of responsibility. So, it it is very important your lawyer know this area of the law and is present to help during the interview.

By Your Attorney

Your lawyer is responsible for, not only challenging errors in the Presentence Report, but also presenting to the judge any mitigating sentencing factors. A few of these factors may be:

- Lack of a prior criminal record;

- A mitigating role in the offense;

- How the victim might have contributed to the offense;

- Past circumstances, such as abuse that lead a defendant to engage in criminal conduct;

- Circumstances at the time of the offense, such as provocation, stress, or emotional problems that might not excuse the crime but might offer an explanation;

- Mental or physical illness; and

- Genuine remorse.

Investigating and presenting your mitigating factors may be the most important thing your lawyer can do for you. This is a process that should start at the absolute beginning of the case.

3. Presentence Report

After the interview, the probation officer prepares a presentence report, or PSR. This document contains information about the offense and the offender as well as the statutory range of punishment. The report should include any bases that exist for imposing a sentence outside of the Guideline range. The probation officer must provide a copy of the PSR to both the defense and prosecution at least 35 days before the sentencing. Then, these parties may submit any factual or legal objections to the report within 14 days.

Objections to the PSR can make a substantial difference in the sentence. A lawyer needs to be abreast of the latest changes in case law, Guideline policy, and local practices.

4. Final Hearing

Steps

It may not be apparent watching a sentencing hearing, but the judge is working through these steps during the hearing:

- Announce the Guidelines pursuant to the PSR and any addenda;

- Consider and rule on any objections to the PSR or addenda;

- Announce the final Guideline range based on the court’s rulings;

- Determine whether a Departure is appropriate;

- Determine whether a Variance is appropriate;

- Determine whether an Adjustment is necessary;

- Pronounce the final sentence; and

- Rule on any final objections.

Evidence

The rules for sentencing hearings are not as formal as the rules for trial proceedings. The court must allow both parties to provide input before imposing the sentence. The court can also allow the parties to call in witnesses or present evidence about disputed facts. The judge has great latitude in deciding what evidence to consider. However, according to the Sentencing Commission, the information presented must be sufficiently “reliable” in order to be considered by the judge.

The Federal Rules of Evidence do not apply during sentencing, meaning:

- Hearsay may be considered;

- “Expert” testimony may be considered with limited qualification;

- The Government may lead witnesses;

- Witness may be allowed to speculate freely; and

- Much of what may not be admissible at trial, may be part of the sentencing hearing.

The “Exclusionary rule” does not apply, so the court can consider evidence that was illegally obtained by the Government.

The judge is not bound by believing evidence Beyond a Reasonable Doubt or even Clear and Convincing Evidence. The judge may determine accusations are true based on a Preponderance of Evidence (the Government convinces the judge that there is a greater than 50% chance that the claim is true). In the Fifth Circuit, the PSR is given the presumption of reliability. Which means, unless a defendant can prove otherwise, the judge can just accept the conclusions contained in the PSR.

Departures and Variances

Although the court must properly calculate and consider the Guidelines, the judge is not required to follow the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. The court can consider a defendant’s background, character, and conduct and impose a sentence either greater than or less than the Guideline range calculated in the PSR. This is achieved through a departure or a variance.

A departure is a sentence outside of the PSR Guideline range based on a specific sentencing guideline or policy written by the U.S. Sentencing Commission. For example, USSG Section 5H1.1 of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines allows for a departure based on old age or on youthfulness.

A variance is a sentence outside of the Sentencing Guidelines based on other factors in the United States Code Chapter 18 Section 3553. For example, a federal court may impose a variance based on the specific circumstances of the defendant’s crime or personal history.

Relevant Conduct

Relevant conduct is a complex idea that is laid out in great detail in the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. The guidelines allow judges to consider the defendant’s actions and omissions in regards to other related crimes or conduct. For example, a defendant may have once been charged with a crime and found “not guilty” or had the charges dismissed. If the judge believes these alleged acts are a part of the same pattern of conduct that led the defendant to their current charge, the judge can take those past charges into consideration when determining the sentence.

The judge can also consider all of the actions the offender performed in preparation for the crime, during the crime, and after the crime to avoid detection. This includes acts that the defendant commanded, caused, or induced from others in relation to their crime. A person may be held responsible for the foreseeable actions of co-defendants or co-conspirators.

Judgment and Sentence

After pronouncing the sentence, the court must complete the “Judgment in a Criminal Case” and the “Statement of Reasons” documents. These reports confirm the sentence that was orally pronounced. The court must also inform the defendant of their right to appeal. From this final judgment, a defendant may appeal.